I first 'met' writer

Zafar Anjum in January 2002, when I took a tentative first step into in Francis Ford Coppola's

zoetrope virtual studios. His thoughtful and balanced critique of my short story paved the way for many years of writerly exchanges and a warm personal friendship. The Internet not only expands our horizons, but is also a great leveller, connecting people from diverse backgrounds and cultures. We lived in different parts of India in those days, came from different generations and spoke different languages. A personal meeting was fated to finally happen over a decade later, but meanwhile, the virtual friendship flourished. As we read and offered constructive suggestions on each other's short stories through the Zoetrope workshops, we bonded over our shared interest in reading and writing. I still remember the characters from his

early stories who stayed with me: the lonely and cantankerous old lady redeemed at last by rather seedy looking 'angels' with grubby fingernails; the young man pondering over old friendships which fizzled out for reasons he cannot fathom; a nervous newly-married man who dies a pathetic and painful death; and more.

Through the years, we shared through e-mails and online chats our writerly disappointments and also the rare little tirumphs that gave us hope to continue struggling. That long wait through many, many rejections before a short story won acceptance from a literary journal; the pressures of bracing oneself to write a major work and then hoping some editor would give it a nod of approval. These experiences also moulded us, and our approach to life and to writing. "You can say I am becoming a recluse, and a more inward person," he once told me. "I am trying to connect more to my inner self and trying to live beyond my ego. I feel happier and calmer this way, and this approach is also closer to my basic nature.This does not mean I am not meeting other folks. I go to select parties and chill out, but not very often."

Years ago, I began saving such thoughtful mails from my handful closest writer friends. I knew they had it in them to soar high, writing more and better stories and books that would would be widely appreciated one day. I remember how I would joke with Zafar that these exchanges would one day lead to the biography of a major literary talent. That day now seems to be dawning.

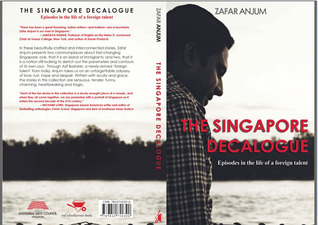

Singapore-based Indian author and journalist Zafar Anjum today has a wide and varied published body of writing to his credit. I'm proud of my first and longest standing writer buddy, and look forward to congratulating him on many, many more books. Zafar recently had two books released:

The Resurgence of Satyam (Random House India) and

The Singapore Decalogue (Red Wheelbarrow Books, Singapore). He has also authored

Kafka and Orwell on China (Samshwords, 2011). His earlier works include a novel (

Of Seminal Fluids, 2000) and a volume of translated poetry (

My Silence Speaks, 2001). He has recently finished his second novel

Murder in Clivesganj, a thriller set in a small town in India, which is awaiting publication. I've had the pleasure of reading excerpts from this literary mystery and hope to see the complete book in print soon.

His short stories have recently appeared in three anthologies,

Love and Lust in Singapore, The Best of Southeast Asian Erotica and

Crime Scene: Singapore. Zafar’s journalism and fiction have appeared in

The South China Morning Post (Hong Kong),

Today (Singapore),

India Se (Singapore),

The Bangkok Post (Thailand),

Jakarta Globe (Indonesia),

The Hindustan Times (India),

The Times of India (India),

Tehelka (India),

The Pioneer (India),

Outlook (India),

Mainstream (India),

China Daily (China),

The Little Magazine (India),

Little India (US),

Malaysiakini.com (Malaysia),

Small Spiral Notebook (US),

Jamini (Bangladesh) and

The Six Seasons Review (Bangladesh), among others.

He is also the founder-editor of Kitaab, a website dedicated to Asian writing in English. Currently, he co-edits a global website for writers, Writers Connect.

The Arts Creation Fund grant from Singapore’s National Arts Council for writing

The Singapore Decalogue came to Zafar from "out of the blue. I had applied without any hope, and I could not believe it when I got it," Zafar says. "There was huge competition. I was the first Indian PR (permanent resident) to get this grant, if I am not mistaken. It gave me confidence and lot of push when I needed it most."

"In this collection of short stories, I have tried to create vignettes of life in Singapore. This is my tribute to this city state, which has built its social capital with great wisdom, civic sense, and quotidian practicality...

"In these stories, I have tried to portray the hopes and frustrations of a few interconnected characters (that was truer for the earlier draft when the characters were varied). The bustling metropolis attracts all kinds of people who want to make a life here. What happens to their dreams? What kind of struggles do they go through? Do they feel alienated? What do they love about the city? And so on.

Through the panoply of characters, mainly built around a main character, Asif Basheer, an aspiring poet from India, I have woven together a web of stories that throw light on various contemporary themes. The initial aspiration, following in the footsteps of Tolstoy and the Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski (especially his film cycle, The Decalogue), was to explore themes based on the Ten Commandments, but I finally transformed the idea. I was anxious, even afraid, that the stories might come across as too moralistic or formulaic if I went down that route. Nevertheless, my moral concerns about making choices in life still shaped and informed the stories in The Singapore Decalogue."

The protagonist in these tales is Asif, a poet. "Whatever poetry he had written had remained unpublished. "In this world, it does not matter what you know. What matters is who you know," Asif tells himself. He comes to Singapore with an attractive job, and great hope that lady luck will smile upon him at last in this land of opportunities. Yet ominous dark clouds creep up to steal his sunshine. His company is under investigation, and tension is in the air. Meanwhile, this good-hearted young man from small town India takes in the sights and sounds of a brave new world. He shares his experiences with his wife Mariam, how "the Singapore he had heard of as a little boy, the place from where the Singapore banana used to come from, was no more a provincial backwater but a new age metropolis; a city put together out of raw jungle by sheer human will and imagination."

With his new friends, Asif explores the wonders of Singapore.He smiles to his pretty Filipina neighbours out of courtesy, hoping to spread positive vibes around him in an alien country. He notes the cool responses to his smiles and to his job application, and knows that the colour of one's skin matters as much and sometimes more, that an impressive resume to wily employers like Mr Fong. Asif'ssensitive mind sees beyond the glitz and glamour and feels for poor bar girls compelled to please shady clients for money they need to support the families they love. Asif knows the money-making culture dominates Singapore, as it does in the rest of the world. Yet he sees the people around him with humane empathy.

Meanwhile, the mysterious Black Monk appears, reappears and vanishes, tossing enigmatic pearls of advice at our hero during major turning points in his life. He compels Asif and the reader to ponder the human dilemma.

Knowing as I do of some of Zafar's personal experiences during the last decade, I can see a little of him and his own perception in some of the characters and situations in these stories. In fact most of us writers put a bit of ourselves into the stories that we write. But Zafar's tales are pure fiction. The characters stand as convincing individuals in their own right. The writer's own ideas enrich a consummately crafted artistic work, while the writer himself remains far in the background as the creator of it all.

During one of our many exchanges, Zafar had said to me," It has definitely porous boundaries, fact and fiction merge. It happens with me too.

Over the years, I have seen that I am able to get into (how successfully--that I don't know) other people's minds more easily and write less personal stories. Maybe that is part of how we grow up as writers. Maybe we get more confident over time..."

I see that growth and confidence happening right now, in this very book.

"I had started

The Singapore Decalogue first," Zafar says. "Meanwhile, I was also chasing the Satyam story. The Satyam scandal became a global business story pretty quickly after it hit the headlines in India in 2009. After all, it was India’s fourth largest outsourcing company and it was also listed on the Nasdaq in the USA. The Indian growth story was being keenly watched in the outside world and Satyam’s fall was not a blip. It grabbed eyeballs everywhere as it seemed to puncture the ‘India Shining’ story outside India. India, which was then a rising and shining outpost of globalization in Asia, suddenly had this blot on its resplendent reputation. Seemingly all was lost but not quite..

Personally, I see the story of Satyam’s turnaround as a positive story. This was a unique example to come from a place where corruption has been seen to be endemic. In the West, many companies have melted away after falling victim to financial scandals. The example of Enron comes to mind. Satyam survived a deadly implosion and how quickly it bounced back on its feet—that is an inspiring story to come from India where some much negativity floats around. That’s why I decided to tell the story of Satyam’s bouncing back."

Zafar and I finally met in the real world in January 2012, when research on the Satyam saga brought him to Bangalore. A warm, soft-spoken man with a sense of self-deprecatory humour, he brought a whiff of fresh air into a world crowded by the self-absorbed. I noted his old-worldy

pehle aap courtesy, no put on airs, but quiet sincereity and straight-from-the-heart goodwill. His sense of fun and adventure peeped out when he ordered pungent Andhra style chicken with 'gunpowder' on the side. There we are dousing the fire on our tongues with ice cream on a cool winter day, while his friend graciously captured the moment with a click.

The Shadow of the Crescent Moon: Fatima Bhutto Penguin/Viking

The Shadow of the Crescent Moon: Fatima Bhutto Penguin/Viking

Association with

Association with

...

...

As we celebrate the 66th anniversary of India’s Independence, many of our compatriots are clamouring for divided identities. The issue of separate statehood for Telangana has reached a feverish pitch, giving a boost to similar demands elsewhere in the country. The cry for Bodoland has resurfaced, Gorkha Janamukti Morcha supporters are calling for a separate Gorkhaland, while the Codava National Council is gearing to press for an autonomous Codava Land. Will the call for a division of Uttar Pradesh build up? When everyone and their neighbours seem to be staking their claim for distinct identities, where will we stand as Indians? Will we support increasingly narrowing sub-divisions and fight among ourselves for shrinking patches of home turf? Or, shall we transcend constricted allegiances and boundaries to become not only Indians, but true citizens of the world? What defines a homeland? Is it ethnicity, language, religion, customs and beliefs? Are we Indians simply because we happened to have been born as citizens of this sovereign republic? Deep inside, do we identify ourselves more strongly as Kannadigas, Punjabis or Marathis, or according to our religious affinities? Where do we really belong?

As we celebrate the 66th anniversary of India’s Independence, many of our compatriots are clamouring for divided identities. The issue of separate statehood for Telangana has reached a feverish pitch, giving a boost to similar demands elsewhere in the country. The cry for Bodoland has resurfaced, Gorkha Janamukti Morcha supporters are calling for a separate Gorkhaland, while the Codava National Council is gearing to press for an autonomous Codava Land. Will the call for a division of Uttar Pradesh build up? When everyone and their neighbours seem to be staking their claim for distinct identities, where will we stand as Indians? Will we support increasingly narrowing sub-divisions and fight among ourselves for shrinking patches of home turf? Or, shall we transcend constricted allegiances and boundaries to become not only Indians, but true citizens of the world? What defines a homeland? Is it ethnicity, language, religion, customs and beliefs? Are we Indians simply because we happened to have been born as citizens of this sovereign republic? Deep inside, do we identify ourselves more strongly as Kannadigas, Punjabis or Marathis, or according to our religious affinities? Where do we really belong?

Despite the challenges of rampant corruption, disorganisation, bureaucracy and inefficiency, India manages to keep going. We Indians seem to have excelled in making our lives work. We survive, and even thrive, in adverse conditions. We deserve a pat on our back for our determination and resilience.

Despite the challenges of rampant corruption, disorganisation, bureaucracy and inefficiency, India manages to keep going. We Indians seem to have excelled in making our lives work. We survive, and even thrive, in adverse conditions. We deserve a pat on our back for our determination and resilience. Vanity Bagh Author:Anees Salim

Vanity Bagh Author:Anees Salim I recently enjoyed an exhibition of photooprahs of Inda by eminent photogrpahers from all over the world. The photographs span several decades, capturing the varied facets of Indian life. Magnum photographers’ vision of India is reflected in their images. Though India’s colour and light are cited as an inspiration to these photographers, their work reveals much more than its surface beauty.

I recently enjoyed an exhibition of photooprahs of Inda by eminent photogrpahers from all over the world. The photographs span several decades, capturing the varied facets of Indian life. Magnum photographers’ vision of India is reflected in their images. Though India’s colour and light are cited as an inspiration to these photographers, their work reveals much more than its surface beauty.

India’s rich legacy of art, architecture, ideas and ideals has been built up over many thousands of years. But today, how many of us pause to appreciate our common cultural inheritance? Our cultural tradition is widely praised in distant foreign lands. It offers humanity a beacon of hope from its dangerous course of rampant greed and aggressive rivalry. Meanwhile, Indians like us focus our energies upon the rat race.

India’s rich legacy of art, architecture, ideas and ideals has been built up over many thousands of years. But today, how many of us pause to appreciate our common cultural inheritance? Our cultural tradition is widely praised in distant foreign lands. It offers humanity a beacon of hope from its dangerous course of rampant greed and aggressive rivalry. Meanwhile, Indians like us focus our energies upon the rat race.